Piaget’s Theory and Stages of Cognitive Development

Saul McLeod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Reviewed by

&

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

Key Features

- Constructivist approach to learning: Piaget believed that children actively construct their understanding of the world rather than passively absorbing information. This emphasizes the child’s role as a “little scientist,” exploring and making sense of their environment.

- Developmental Stages: Piaget proposed four sequential stages of cognitive development, each marked by distinct thinking patterns, progressing from infancy to adolescence.

- Schemas: Schemas are mental frameworks that help individuals organize and interpret information. As children grow and learn, their schemas become more numerous and sophisticated, allowing for more complex understanding of the world.

- Assimilation: Incorporating new information into preexisting ideas and schemas.

- Accommodation: Modifying existing schemas or creating new ones to fit new information.

- Equilibration: This is how children progress through cognitive developmental stages. It involves balancing assimilation and accommodation, driving the shift from one stage of thought to the next as children encounter and resolve cognitive conflicts.

Stages of Development

Jean Piaget’s theory of cognitive development suggests that children move through four different stages of intellectual development which reflect the increasing sophistication of children’s thought

Each child goes through the stages in the same order (but not all at the same rate), and child development is determined by biological maturation and interaction with the environment.

At each stage of development, the child’s thinking is qualitatively different from the other stages, that is, each stage involves a different type of intelligence.

| Stage | Age | Goal |

|---|

| Sensorimotor | Birth to 18-24 months | Object permanence |

| Preoperational | 2 to 7 years old | Symbolic thought |

| Concrete operational | Ages 7 to 11 years | Logical thought |

| Formal operational | Adolescence to adulthood | Scientific reasoning |

Piaget’s 4 Stages of Cognitive Development

Although no stage can be missed out, there are individual differences in the rate at which children progress through stages, and some individuals may never attain the later stages.

Piaget did not claim that a particular stage was reached at a certain age – although descriptions of the stages often include an indication of the age at which the average child would reach each stage.

The Sensorimotor Stage

Ages: Birth to 2 Years

During the sensorimotor stage (birth to age 2) infants develop basic motor skills and learn to perceive and interact with their environment through physical sensations and body coordination.

Major Characteristics and Developmental Changes:

- The infant learns about the world through their senses and through their actions (moving around and exploring their environment).

- During the sensorimotor stage, a range of cognitive abilities develop. These include: object permanence; self-recognition (the child realizes that other people are separate from them); deferred imitation; and representational play.

- Cognitive abilities relate to the emergence of the general symbolic function, which is the capacity to represent the world mentally

- At about 8 months, the infant will understand the permanence of objects and that they will still exist even if they can’t see them, and the infant will search for them when they disappear.

At the beginning of this stage, the infant lives in the present. It does not yet have a mental picture of the world stored in its memory, so it does not have a sense of object permanence.

If it cannot see something, then it does not exist. This is why you can hide a toy from an infant, while it watches, but it will not search for the object once it has gone out of sight.

The main achievement during this stage is object permanence – knowing that an object still exists, even if it is hidden. It requires the ability to form a mental representation (i.e., a schema) of the object.

Towards the end of this stage the general symbolic function begins to appear where children show in their play that they can use one object to stand for another. Language starts to appear because they realise that words can be used to represent objects and feelings.

The child begins to be able to store information about the world, recall it, and label it.

Individual Differences

- Cultural Practices: In some cultures, babies are carried on their mothers’ backs throughout the day. This constant physical contact and varied stimuli can influence how a child perceives their environment and their sense of object permanence.

- Gender Norms: Toys assigned to babies can differ based on gender expectations. A boy might be given more cars or action figures, while a girl might receive dolls or kitchen sets. This can influence early interactions and sensory explorations.

The Preoperational Stage

Ages: 2 – 7 Years

Piaget’s second stage of intellectual development is the preoperational stage, which occurs between 2 and 7 years. At the beginning of this stage, the child does not use operations (a set of logical rules), so thinking is influenced by how things look or appear to them rather than logical reasoning.

For example, a child might think a tall, thin glass contains more liquid than a short, wide glass, even if both hold the same amount, because they focus on the height rather than considering both dimensions.

Furthermore, the child is egocentric; he assumes that other people see the world as he does, as shown in the Three Mountains study.

As the preoperational stage develops, egocentrism declines, and children begin to enjoy the participation of another child in their games, and let’s pretend play becomes more important.

Toddlers often pretend to be people they are not (e.g. superheroes, policemen), and may play these roles with props that symbolize real-life objects. Children may also invent an imaginary playmate.

Major Characteristics and Developmental Changes:

- Toddlers and young children acquire the ability to internally represent the world through language and mental imagery.

- During this stage, young children can think about things symbolically. This is the ability to make one thing, such as a word or an object, stand for something other than itself.

- A child’s thinking is dominated by how the world looks, not how the world is. It is not yet capable of logical (problem-solving) type of thought.

- Moreover, the child has difficulties with class inclusion; he can classify objects but cannot include objects in sub-sets, which involves classifying objects as belonging to two or more categories simultaneously.

- Infants at this stage also demonstrate animism. This is the tendency for the child to think that non-living objects (such as toys) have life and feelings like a person’s.

By 2 years, children have made some progress toward detaching their thoughts from the physical world. However, have not yet developed logical (or “operational”) thought characteristics of later stages.

Thinking is still intuitive (based on subjective judgments about situations) and egocentric (centered on the child’s own view of the world).

Individual Differences

- Cultural Storytelling: Different cultures have unique stories, myths, and folklore. Children from diverse backgrounds might understand and interpret symbolic elements differently based on their cultural narratives.

- Race & Representation: A child’s racial identity can influence how they engage in pretend play. For instance, a lack of diverse representation in media and toys might lead children of color to recreate scenarios that don’t reflect their experiences or background.

The Concrete Operational Stage

Ages: 7 – 11 Years

By the beginning of the concrete operational stage, the child can use operations (a set of logical rules) so they can conserve quantities, realize that people see the world in a different way (decentring), and demonstrate improvement in inclusion tasks.

Children still have difficulties with abstract thinking.

Major Characteristics and Developmental Changes:

- During this stage, children begin to think logically about concrete events.

- Children begin to understand the concept of conservation; understanding that, although things may change in appearance, certain properties remain the same.

- During this stage, children can mentally reverse things (e.g., picture a ball of plasticine returning to its original shape).

- During this stage, children also become less egocentric and begin to think about how other people might think and feel.

The stage is called concrete because children can think logically much more successfully if they can manipulate real (concrete) materials or pictures of them.

Piaget considered the concrete stage a major turning point in the child’s cognitive development because it marks the beginning of logical or operational thought. This means the child can work things out internally in their head (rather than physically try things out in the real world).

Children can conserve number (age 6), mass (age 7), and weight (age 9). Conservation is the understanding that something stays the same in quantity even though its appearance changes.

But operational thought is only effective here if the child is asked to reason about materials that are physically present. Children at this stage will tend to make mistakes or be overwhelmed when asked to reason about abstract or hypothetical problems.

Individual Differences

- Cultural Context in Conservation Tasks: In a society where resources are scarce, children might demonstrate conservation skills earlier due to the cultural emphasis on preserving and reusing materials.

- Gender & Learning: Stereotypes about gender abilities, like “boys are better at math,” can influence how children approach logical problems or classify objects based on perceived gender norms.

The Formal Operational Stage

Ages: 12 and Over

The formal operational period begins at about age 11. As adolescents enter this stage, they gain the ability to think abstractly, the ability to combine and classify items in a more sophisticated way, and the capacity for higher-order reasoning.

Adolescents can think systematically and reason about what might be as well as what is (not everyone achieves this stage). This allows them to understand politics, ethics, and science fiction, as well as to engage in scientific reasoning.

Adolescents can deal with abstract ideas; for example, they can understand division and fractions without having to actually divide things up and solve hypothetical (imaginary) problems.

Major Characteristics and Developmental Changes:

- Concrete operations are carried out on physical objects, whereas formal operations are carried out on ideas. Formal operational thought is entirely freed from physical and perceptual constraints.

- During this stage, adolescents can deal with abstract ideas (e.g., they no longer need to think about slicing up cakes or sharing sweets to understand division and fractions).

- They can follow the form of an argument without having to think in terms of specific examples.

- Adolescents can deal with hypothetical problems with many possible solutions. For example, if asked, ‘What would happen if money were abolished in one hour?’ they could speculate about many possible consequences.

- Piaget described reflective abstraction as the process by which individuals become aware of and reflect upon their own cognitive actions or operations (metacognition).

From about 12 years, children can follow the form of a logical argument without reference to its content. During this time, people develop the ability to think about abstract concepts, and logically test hypotheses.

This stage sees the emergence of scientific thinking, formulating abstract theories and hypotheses when faced with a problem.

Individual Differences

- Culture & Abstract Thinking: Cultures emphasize different kinds of logical or abstract thinking. For example, in societies with a strong oral tradition, the ability to hold complex narratives might develop prominently.

- Gender & Ethics: Discussions about morality and ethics can be influenced by gender norms. For instance, in some cultures, girls might be encouraged to prioritize community harmony, while boys might be encouraged to prioritize individual rights.

Piaget’s Theory

- Piaget’s theory places a strong emphasis on the active role that children play in their own cognitive development.

- According to Piaget, children are not passive recipients of information; instead, they actively explore and interact with their surroundings.

- This active engagement with the environment is crucial because it allows them to gradually build their understanding of the world.

1. How Piaget Developed the Theory

Piaget was employed at the Binet Institute in the 1920s, where his job was to develop French versions of questions on English intelligence tests. He became intrigued with the reasons children gave for their wrong answers to the questions that required logical thinking.

He believed that these incorrect answers revealed important differences between the thinking of adults and children.

Piaget branched out on his own with a new set of assumptions about children’s intelligence:

- Children’s intelligence differs from an adult’s in quality rather than in quantity. This means that children reason (think) differently from adults and see the world in different ways.

- Children actively build up their knowledge about the world. They are not passive creatures waiting for someone to fill their heads with knowledge.

- The best way to understand children’s reasoning is to see things from their point of view.

Piaget did not want to measure how well children could count, spell or solve problems as a way of grading their I.Q. What he was more interested in was the way in which fundamental concepts like the very idea of number, time, quantity, causality, justice, and so on emerged.

Piaget studied children from infancy to adolescence using naturalistic observation of his own three babies and sometimes controlled observation too. From these, he wrote diary descriptions charting their development.

He also used clinical interviews and observations of older children who were able to understand questions and hold conversations.

2. Piaget’s Theory Differs From Others In Several Ways:

Piaget’s (1936, 1950) theory of cognitive development explains how a child constructs a mental model of the world.

He disagreed with the idea that intelligence was a fixed trait, and regarded cognitive development as a process that occurs due to biological maturation and interaction with the environment.

Children’s ability to understand, think about, and solve problems in the world develops in a stop-start, discontinuous manner (rather than gradual changes over time).

- It is concerned with children, rather than all learners.

- It focuses on development, rather than learning per se, so it does not address learning of information or specific behaviors.

- It proposes discrete stages of development, marked by qualitative differences, rather than a gradual increase in number and complexity of behaviors, concepts, ideas, etc.

The goal of the theory is to explain the mechanisms and processes by which the infant, and then the child, develops into an individual who can reason and think using hypotheses.

To Piaget, cognitive development was a progressive reorganization of mental processes as a result of biological maturation and environmental experience.

Children construct an understanding of the world around them, then experience discrepancies between what they already know and what they discover in their environment.

3. Schemas

A schema is a mental framework or concept that helps us organize and interpret information. It’s like a mental file folder where we store knowledge about a particular object, event, or concept.

According to Piaget (1952), schemas are fundamental building blocks of cognitive development. They are constantly being created, modified, and reorganized as we interact with the world.

Wadsworth (2004) suggests that schemata (the plural of schema) be thought of as “index cards” filed in the brain, each one telling an individual how to react to incoming stimuli or information.

According to Piaget, we are born with a few primitive schemas, such as sucking, which give us the means to interact with the world. These initial schemas are physical, but as the child develops, they become mental schemas.

- Babies have a sucking reflex, triggered by something touching their lips. This corresponds to a “sucking schema.”

- The grasping reflex, elicited when something touches the palm of a baby’s hand, represents another innate schema.

- The rooting reflex, where a baby turns its head towards something which touches its cheek, is also considered an innate schema.

When Piaget discussed the development of a person’s mental processes, he referred to increases in the number and complexity of the schemata that the person had learned.

When a child’s existing schemas are capable of explaining what it can perceive around it, it is said to be in a state of equilibrium, i.e., a state of cognitive (i.e., mental) balance.

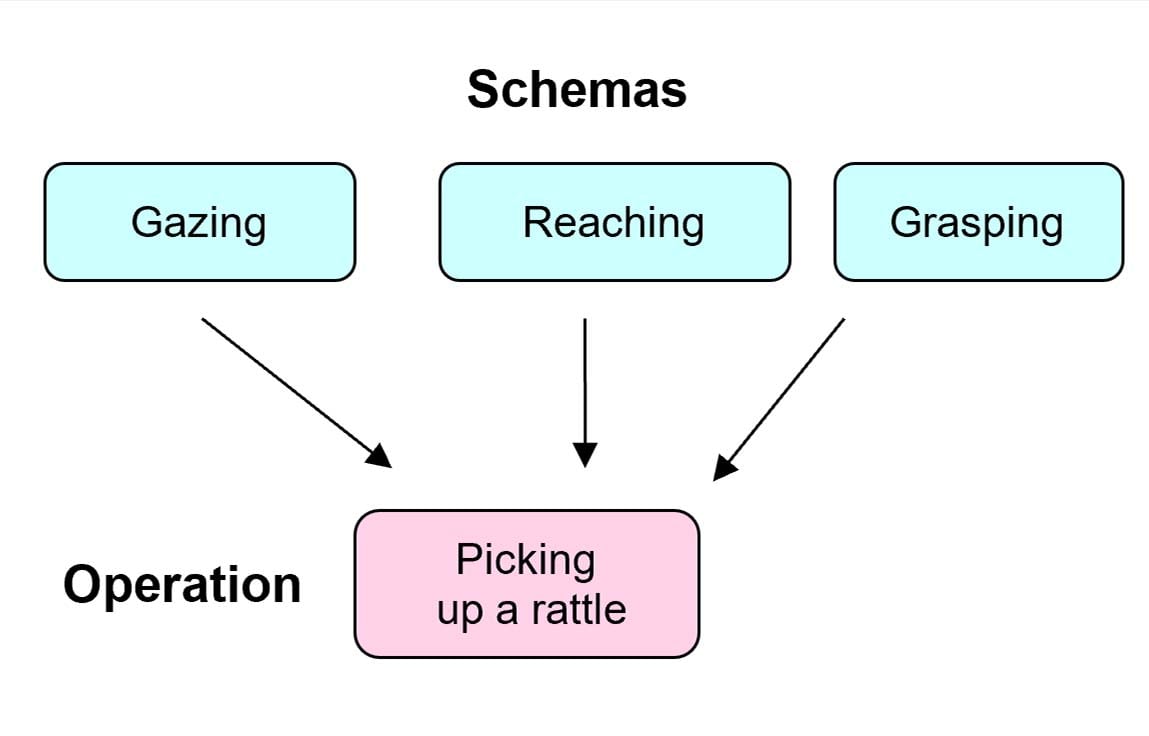

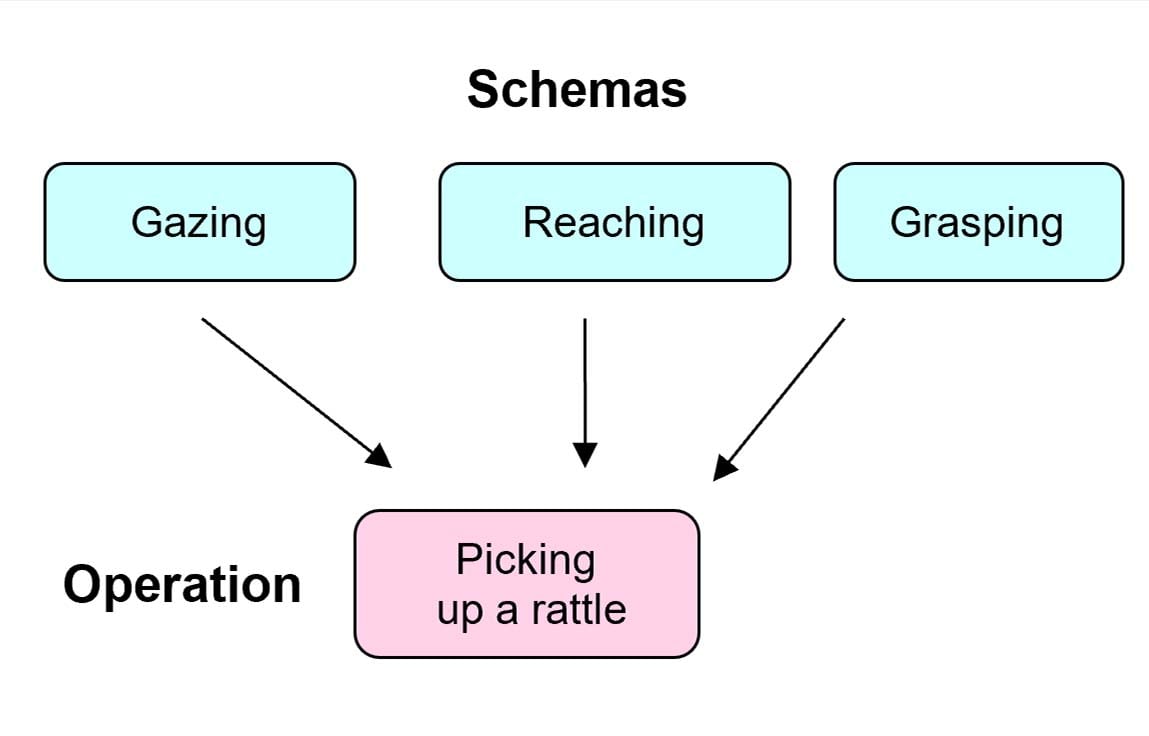

Operations are more sophisticated mental structures that allow us to combine schemas in a logical (reasonable) way. For example, picking up a rattle would combine three schemas, gazing, reaching and grasping.

As children grow, they can carry out more complex operations and begin to imagine hypothetical (imaginary) situations.

Operations are learned through interaction with other people and the environment, and they represent a key advancement in cognitive development beyond simple schemas.

As children grow and interact with their environment, these basic schemas become more complex and numerous, and new schemas are developed through the processes of assimilation and accommodation.

4. The Process of Adaptation

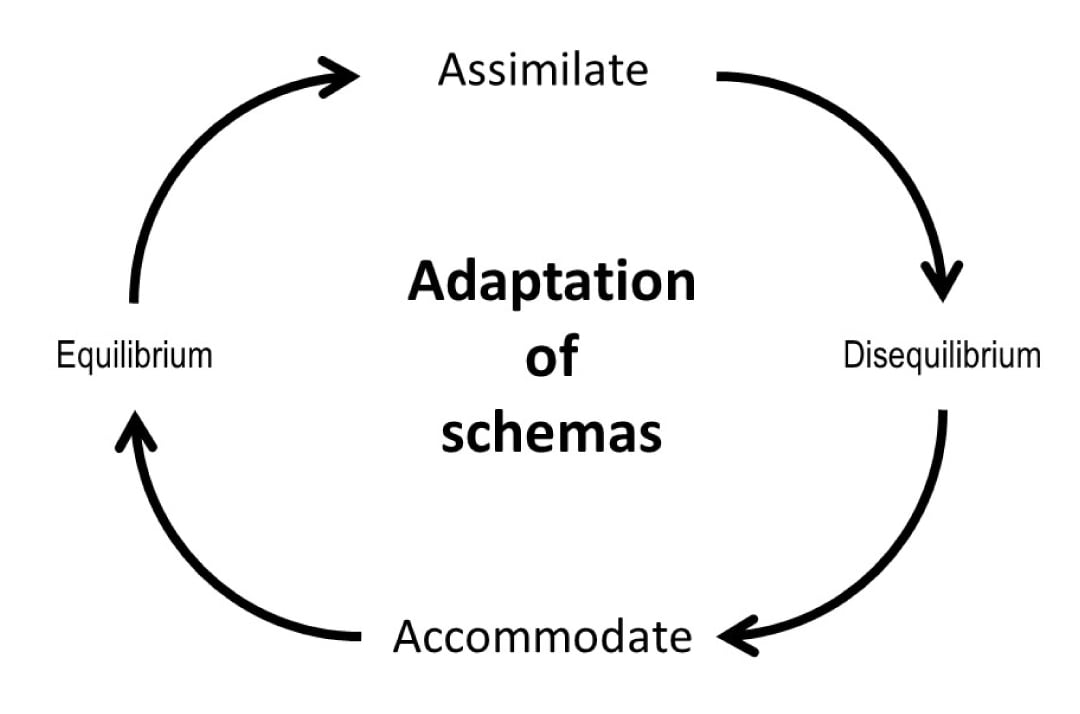

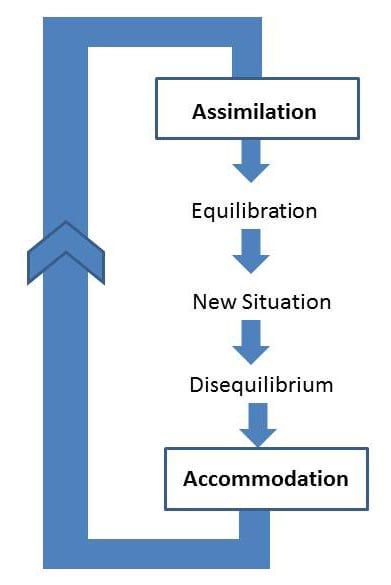

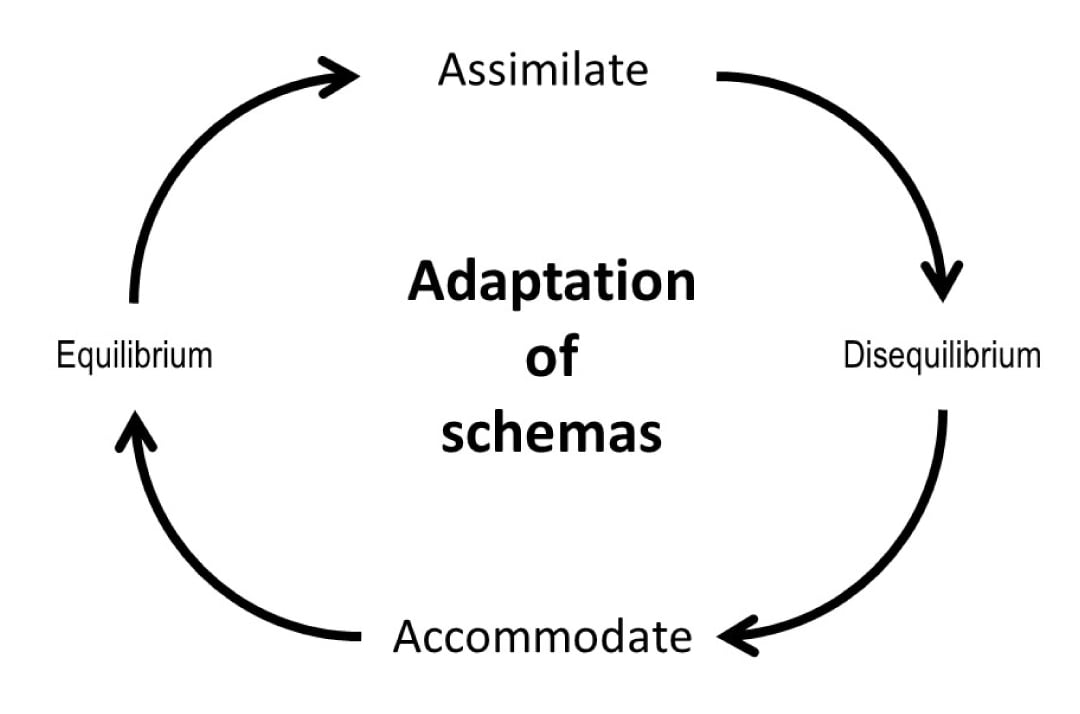

Piaget (1952) believed child development results from maturation and environmental interaction. Adaptation is the process of changing mental models to match reality, achieved through assimilation and accommodation.

- Assimilation is fitting new information into existing schemas without changing one’s understanding. For example, a child who has only seen small dogs might call a cat a “dog” due to similar features like fur, four legs, and a tail.

- Accommodation occurs when existing schemas must be revised to incorporate new information. For instance, a child who believes all animals have four legs would need to accommodate their schema upon seeing a snake. A baby tries to use the same grasping schema to pick up a very small object. It doesn’t work. The baby then changes the schema using the forefinger and thumb to pick up the object.

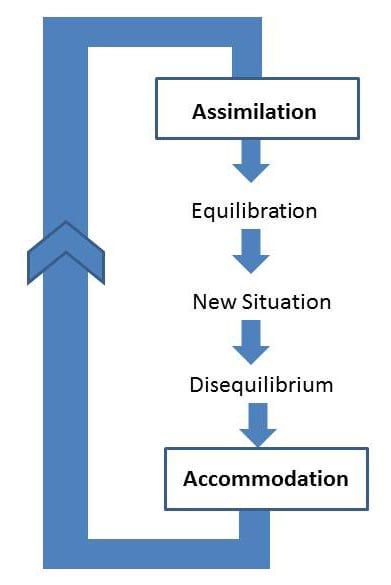

When schemas explain our perceptions, we’re in equilibration. New, unexplainable situations create disequilibrium, motivating learning. This cognitive conflict, where contradictory views exist, drives development.

Piaget viewed intellectual growth as an adaptation to the world through assimilation, accommodation, and equilibration. These processes are continuous and interactive, allowing schemas to evolve and become more sophisticated.

Jean Piaget (1952; see also Wadsworth, 2004) viewed intellectual growth as a process of adaptation (adjustment) to the world. This happens through assimilation, accommodation, and equilibration.

5. Equilibration

Piaget (1985) believed that all human thought seeks order and is uncomfortable with contradictions and inconsistencies in knowledge structures. In other words, we seek “equilibrium” in our cognitive structures.

Equilibrium occurs when a child’s schemas can deal with most new information through assimilation. However, an unpleasant state of disequilibrium occurs when new information cannot be fitted into existing schemas (assimilation).

Piaget believed that cognitive development did not progress at a steady rate, but rather in leaps and bounds. Equilibration is the force which drives the learning process as we do not like to be frustrated and will seek to restore balance by mastering the new challenge (accommodation).

Once the new information is acquired the process of assimilation with the new schema will continue until the next time we need to make an adjustment to it.

Equilibration is a regulatory process that maintains a balance between assimilation and accommodation to facilitate cognitive growth. Think of it this way: We can’t merely assimilate all the time; if we did, we would never learn any new concepts or principles.

Everything new we encountered would just get put in the same few “slots” we already had. Neither can we accommodate all the time; if we did, everything we encountered would seem new; there would be no recurring regularities in our world. We’d be exhausted by the mental effort!

Applications to Education

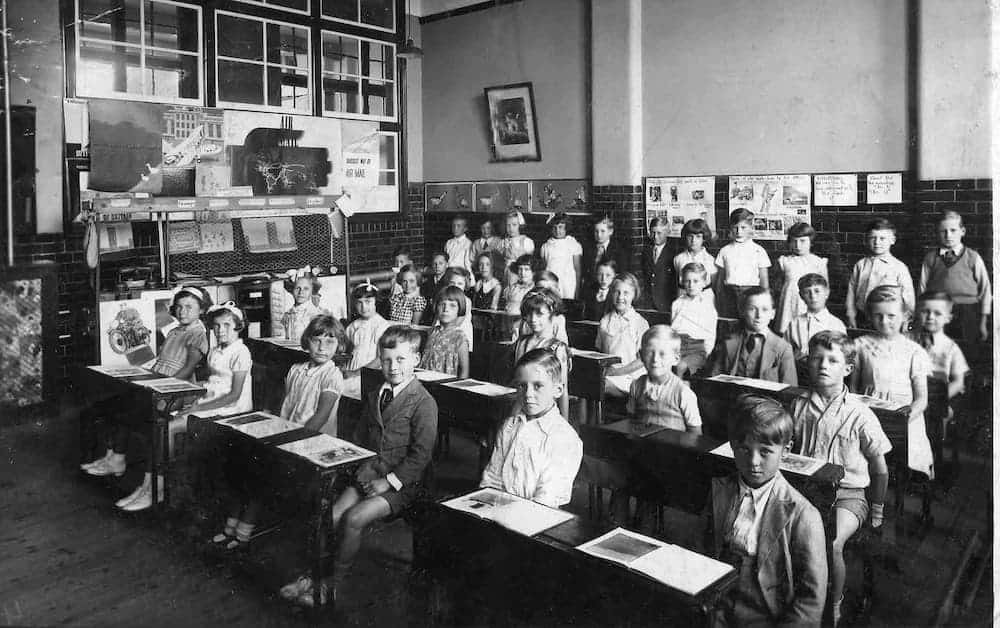

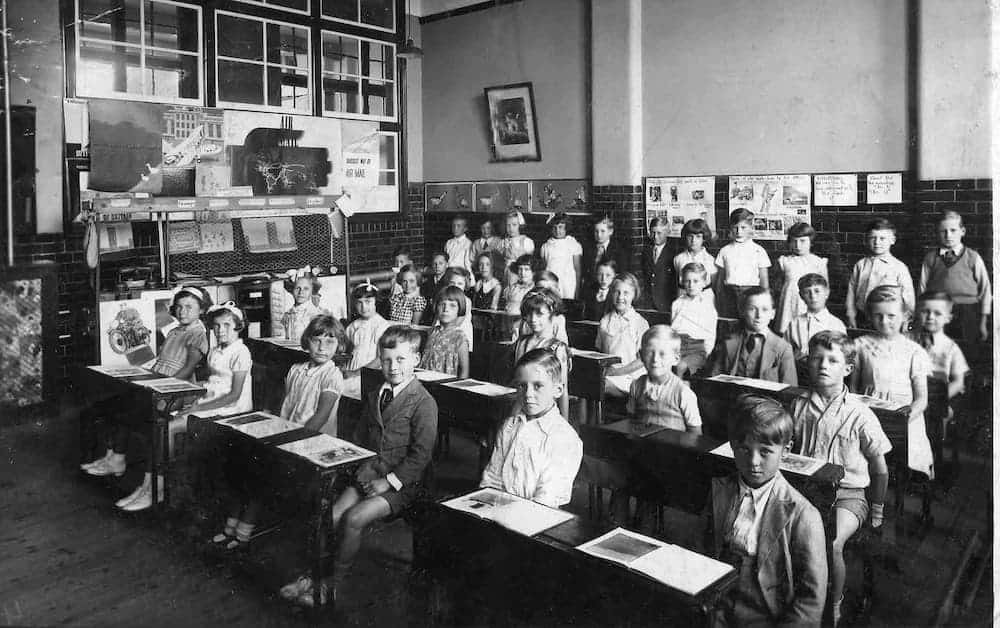

Think of old black-and-white films you’ve seen where children sat in rows at desks with inkwells. They learned by rote, all chanting in unison in response to questions set by an authoritarian figure like Miss Trunchbull in Matilda.

Children who were unable to keep up were seen as slacking and would be punished by variations on the theme of corporal punishment. Yes, it really did happen and in some parts of the world still does today.

Piaget is partly responsible for the change that occurred in the 1960s and for your relatively pleasurable and pain-free school days!

“Children should be able to do their own experimenting and their own research. Teachers, of course, can guide them by providing appropriate materials, but the essential thing is that in order for a child to understand something, he must construct it himself, he must re-invent it. Every time we teach a child something, we keep him from inventing it himself. On the other hand that which we allow him to discover by himself will remain with him visibly”.

Piaget (1972, p. 27)

Plowden Report

Piaget (1952) did not explicitly relate his theory to education, although later researchers have explained how features of Piaget’s theory can be applied to teaching and learning.

Piaget has been extremely influential in developing educational policy and teaching practice. For example, a review of primary education by the UK government in 1966 was based strongly on Piaget’s theory. The result of this review led to the publication of the Plowden Report (1967).

In the 1960s the Plowden Committee investigated the deficiencies in education and decided to incorporate many of Piaget’s ideas into its final report published in 1967, even though Piaget’s work was not really designed for education.

The report makes three Piaget-associated recommendations:

- Children should be given individual attention and it should be realized that they need to be treated differently.

- Children should only be taught things that they are capable of learning

- Children mature at different rates and the teacher needs to be aware of the stage of development of each child so teaching can be tailored to their individual needs.

The report’s recurring themes are individual learning, flexibility in the curriculum, the centrality of play in children’s learning, the use of the environment, learning by discovery and the importance of the evaluation of children’s progress – teachers should “not assume that only what is measurable is valuable.”

Discovery learning, the idea that children learn best through doing and actively exploring, was seen as central to the transformation of the primary school curriculum.

How to teach

Learning should be student-centered and accomplished through active discovery in the classroom. The teacher’s role is to facilitate learning rather than direct tuition.

Because Piaget’s theory is based upon biological maturation and stages, the notion of “readiness” is important. Readiness concerns when certain information or concepts should be taught.

According to Piaget’s theory, children should not be taught certain concepts until they have reached the appropriate stage of cognitive development.

Consequently, education should be stage-specific, with curricula developed to match the age and stage of thinking of the child. For example, abstract concepts like algebra or atomic structure are not suitable for primary school children.

Assimilation and accommodation require an active learner, not a passive one, because problem-solving skills cannot be taught, they must be discovered (Piaget, 1958).

Therefore, teachers should encourage the following within the classroom:

- Consider the stages of cognitive development: Educational programs should be designed to correspond to Piaget’s stages of development. For example, a child in the concrete operational stage should not be taught abstract concepts and should be given concrete aid such as tokens to count with.

- Provide concrete experiences before abstract concepts: Especially for younger children, ensure they have hands-on experiences with concepts before introducing more abstract representations.

- Provide challenges that promote growth without causing frustration: Devising situations that present useful problems and create disequilibrium in the child.

- Focus on the process of learning rather than the end product: Instead of checking if children have the right answer, the teacher should focus on the students’ understanding and the processes they used to arrive at the answer.

- Encourage active learning: Learning must be active (discovery learning). Children should be encouraged to discover for themselves and to interact with the material instead of being given ready-made knowledge. Using active methods that require rediscovering or reconstructing “truths.”

- Foster social interaction: Using collaborative, as well as individual activities (so children can learn from each other). Implement cooperative learning activities, such as group problem-solving tasks or role-playing scenarios.

- Differentiated teaching: Adapt lessons to suit the needs of the individual child. For example, observe a child’s ability to classify objects by color, shape, and size. If they can easily sort by one attribute but struggle with multiple attributes, tailor future activities to gradually increase complexity, such as sorting buttons first by color, then by color and size together.

- Providing support for the “spontaneous research” of the child: Provide opportunities and resources for children to explore topics of their own interest, encouraging their natural curiosity and self-directed learning. Create a “Wonder Wall” in the classroom where children can post questions about topics that interest them.

Classroom Activities

Sensorimotor Stage (0-2 years):

- Object Permanence Games: Play peek-a-boo or hide toys under a blanket to help babies understand that objects still exist even when they can’t see them.

- Sensory Play: Activities like water play, sand play, or playdough encourage exploration through touch.

- Imitation: Children at this age love to imitate adults. Use imitation as a way to teach new skills.

Preoperational Stage (2-7 years):

- Role Playing: Set up pretend play areas where children can act out different scenarios, such as a kitchen, hospital, or market.

- Use of Symbols: Encourage drawing, building, and using props to represent other things.

- Hands-on Activities: Children should interact physically with their environment, so provide plenty of opportunities for hands-on learning.

- Egocentrism Activities: Use exercises that highlight different perspectives. For instance, having two children sit across from each other with an object in between and asking them what the other sees.

Concrete Operational Stage (7-11 years):

- Classification Tasks: Provide objects or pictures to group, based on various characteristics.

- Hands-on Experiments: Introduce basic science experiments where they can observe cause and effect, like a simple volcano with baking soda and vinegar.

- Logical Games: Board games, puzzles, and logic problems help develop their thinking skills.

- Conservation Tasks: Use experiments to showcase that quantity doesn’t change with alterations in shape, such as the classic liquid conservation task using differently shaped glasses.

Formal Operational Stage (11 years and older):

- Hypothesis Testing: Encourage students to make predictions and test them out.

- Abstract Thinking: Introduce topics that require abstract reasoning, such as algebra or ethical dilemmas.

- Problem Solving: Provide complex problems and have students work on solutions, integrating various subjects and concepts.

- Debate and Discussion: Encourage group discussions and debates on abstract topics, highlighting the importance of logic and evidence.

- Feedback and Questioning: Use open-ended questions to challenge students and promote higher-order thinking. For instance, rather than asking, “Is this the right answer?”, ask, “How did you arrive at this conclusion?”

Individual Differences

While Piaget’s stages offer a foundational framework, they are not universally experienced in the same way by all children.

Social identities play a critical role in shaping cognitive development, necessitating a more nuanced and culturally responsive approach to understanding child development.

Piaget’s stages may manifest differently based on social identities like race, gender, and culture:

- Race & Teacher Interactions: A child’s race can influence teacher expectations and interactions. For example, racial biases can lead to children of color being perceived as less capable or more disruptive, influencing their cognitive challenges and support.

- Racial and Cultural Stereotypes: These can affect a child’s self-perception and self-efficacy. For instance, stereotypes about which racial or cultural groups are “better” at certain subjects can influence a child’s self-confidence and, subsequently, their engagement in that subject.

- Gender & Peer Interactions: Children learn gender roles from their peers. Boys might be mocked for playing “girl games,” and girls might be excluded from certain activities, influencing their cognitive engagements.

- Language: Multilingual children might navigate the stages differently, especially if their home language differs from their school language. The way concepts are framed in different languages can influence cognitive processing. Cultural idioms and metaphors can shape a child’s understanding of concepts and their ability to use symbolic representation, especially in the pre-operational stage.

Overcoming Challenges and Barriers to Implementation

Balancing play and curriculum

- Purposeful Play: Ensuring that play is not just free time but a structured learning experience requires careful planning. Educators must identify clear learning objectives and create play environments that facilitate these goals.

- Alignment with Standards: Striking a balance between child-initiated play and curriculum expectations can be challenging. Educators need to find ways to integrate play-based learning with broader educational goals and standards.

- Pace of Learning: The curriculum’s focus on specific content by certain ages can create pressure to accelerate student learning, potentially contradicting Piaget’s notion of developmental stages. Teachers should regularly assess students’ understanding to identify areas where they need more support or challenge.

- Assessment Focus: The emphasis on standardized testing can shift the focus from process-oriented learning (as Piaget advocated) to outcome-based teaching. Educators should use assessments that reflect real-world tasks and allow students to demonstrate their understanding in multiple ways.

Parents

- Parental Expectations: Some parents may have misconceptions about play-based learning, believing it to be less rigorous than traditional instruction. Educators may need to address these concerns and communicate the value of play.

- Parental Involvement: Involving parents in understanding Piaget’s theory can foster consistency between home and school environments. Providing resources and information to parents about child development can empower them to support their child’s learning at home.

Other challenges

- Individual Differences: Piaget emphasized individual differences in cognitive development, but classrooms often have diverse learners. Meeting the needs of all students while maintaining a play-based approach can be demanding.

- Time Constraints: In some educational settings, there may be pressure to cover specific content or prepare students for standardized tests. Prioritizing play-based learning within these constraints can be difficult.

- Cultural Sensitivity: Recognizing and respecting cultural differences is essential. Piaget’s theory may need to be adapted to fit the specific cultural context of the children being taught.

Can Piaget’s Ideas Be Applied to Children with Special Educational Needs and Disabilities?

Yes, Piaget’s ideas can be adapted to support children with special educational needs and disabilities (SEND), though with important considerations:

- Individualized Approach: Tailor learning experiences to each child’s unique strengths, needs, and interests, recognizing that development may not follow typical patterns or timelines (Daniels & Diack, 1977).

- Concrete Learning Experiences: Provide hands-on, multisensory activities to support concept exploration, particularly beneficial for children with learning difficulties or sensory impairments (Lee & Zentall, 2012).

- Gradual Scaffolding: Break down tasks into manageable steps and provide appropriate support to help children progress through developmental stages at their own pace (Morra & Borella, 2015).

- Flexible Assessment: Modify Piagetian tasks to accommodate different abilities and communication methods, using multiple assessment approaches.

- Strengths-Based Focus: Emphasize children’s capabilities rather than deficits, using Piaget’s concepts to identify and build upon existing cognitive strengths.

- Interdisciplinary Approach: Combine Piagetian insights with specialized knowledge from fields like occupational therapy and speech-language pathology.

While Piaget’s theory offers valuable insights, it should be part of a broader, evidence-based approach that recognizes the diverse factors influencing development in children with SEND.

Social Media (Digital Learning)

Jean Piaget could not have anticipated the expansive digital age we now live in.

Today, knowledge dissemination and creation are democratized by the Internet, with platforms like blogs, wikis, and social media allowing for vast collaboration and shared knowledge. This development has prompted a reimagining of the future of education.

Classrooms, traditionally seen as primary sites of learning, are being overshadowed by the rise of mobile technologies and platforms like MOOCs (Passey, 2013).

The millennial generation, the first to grow up with cable TV, the internet, and cell phones, relies heavily on technology.

They view it as an integral part of their identity, with most using it extensively in their daily lives, from keeping in touch with loved ones to consuming news and entertainment (Nielsen, 2014).

Social media platforms offer a dynamic environment conducive to Piaget’s principles. These platforms allow interactions that nurture knowledge evolution through cognitive processes like assimilation and accommodation.

They emphasize communal interaction and shared activity, fostering both cognitive and socio-cultural constructivism. This shared activity promotes understanding and exploration beyond individual perspectives, enhancing social-emotional learning (Gehlbach, 2010).

A standout advantage of social media in an educational context is its capacity to extend beyond traditional classroom confines. As the material indicates, these platforms can foster more inclusive learning, bridging diverse learner groups.

This inclusivity can equalize learning opportunities, potentially diminishing biases based on factors like race or socio-economic status, resonating with Kegan’s (1982) concept of “recruitability.”

However, there are challenges. While social media’s potential in learning is vast, its practical application necessitates intention and guidance. Cuban, Kirkpatrick, and Peck (2001) note that certain educators and students are hesitant about integrating social media into educational contexts.

This hesitancy can stem from technological complexities or potential distractions. Yet, when harnessed effectively, social media can provide a rich environment for collaborative learning and interpersonal development, fostering a deeper understanding of content.

In essence, the rise of social media aligns seamlessly with constructivist philosophies. Social media platforms act as tools for everyday cognition, merging daily social interactions with the academic world, and providing avenues for diverse, interactive, and engaging learning experiences.

Criticisms of Jean Piaget’s Theories and Concepts

Criticisms of Research Methods

- Small sample size: Piaget often used small, non-representative samples, frequently including only his own children or those from similar backgrounds (European children from families of high socio-economic status). This limits the generalizability of his findings (Lourenço & Machado, 1996).

- Potential researcher bias: Piaget’s methods, including studying his own children and conducting solo observations, risked subjective interpretation. The lack of inter-rater reliability and potential issues with clinical interviews (e.g., children misunderstanding questions or trying to please the experimenter) may have led to biased or inaccurate conclusions. Using multiple researchers and more standardized methods could have improved reliability (Donaldson, 1978).

- Age-related issues : Some critics argue that Piaget underestimated the cognitive abilities of younger children. This may be due to the complex language used in his tasks, which could have masked children’s true understanding.

- Cultural limitations: Piaget’s research was primarily conducted with Western, educated children from relatively affluent backgrounds. This raises questions about the universality of his developmental stages across different cultures (Rogoff, 2003).

- Task design: Some of Piaget’s tasks may have been too abstract or removed from children’s everyday experiences. This could have led to underestimating children’s actual cognitive abilities in more familiar contexts. As several studies have shown Piaget underestimated the abilities of children because his tests were sometimes confusing or difficult to understand (e.g., Hughes , 1975).

Challenges to Key Concepts and Theories

Fixed developmental stages

Are the stages real? Vygotsky and Bruner would rather not talk about stages at all, preferring to see development as a continuous process.

Others have queried the age ranges of the stages. Some studies have shown that progress to the formal operational stage is not guaranteed.

For example, Keating (1979) reported that 40-60% of college students fail at formal operational tasks, and Dasen (1994) states that only one-third of adults ever reach the formal operational stage.

Current developmental psychology has moved beyond seeing development as progressing through discrete, universal stages (as Piaget proposed) to view it as a more gradual, variable process influenced by social, genetic, and cultural factors.

Current perspectives acknowledge greater variability in the timing and sequence of developmental milestones.

There’s greater recognition of the brain’s plasticity and the potential for cognitive growth throughout the lifespan.

This challenges the idea of fixed developmental endpoints proposed in stage theories.

Culture and individual differences

The fact that the formal operational stage is not reached in all cultures and not all individuals within cultures suggests that it might not be biologically based.

- According to Piaget, the rate of cognitive development cannot be accelerated as it is based on biological processes however, direct tuition can speed up the development which suggests that it is not entirely based on biological factors.

- Because Piaget concentrated on the universal stages of cognitive development and biological maturation, he failed to consider the effect that the social setting and culture may have on cognitive development.

Cross-cultural studies show that the stages of development (except the formal operational stage) occur in the same order in all cultures suggesting that cognitive development is a product of a biological maturation process.

However, the age at which the stages are reached varies between cultures and individuals which suggests that social and cultural factors and individual differences influence cognitive development.

Dasen (1994) cites studies he conducted in remote parts of the central Australian desert with 8—to 14-year-old Indigenous Australians.

He gave them conservation of liquid tasks and spatial awareness tasks. He found that the ability to conserve came later in the Aboriginal children, between the ages of 10 and 13 (as opposed to between 5 and 7, with Piaget’s Swiss sample).

However, he found that spatial awareness abilities developed earlier among Aboriginal children than among Swiss children.

Such a study demonstrates that cognitive development is not purely dependent on maturation but on cultural factors as well—spatial awareness is crucial for nomadic groups of people.

Underemphasis on social and emotional factors

While Piaget’s theory focuses primarily on individual cognitive development, it arguably underestimates the crucial role of social and emotional factors.

Lev Vygotsky, a contemporary of Piaget, emphasized the social nature of learning in his sociocultural theory.

Vygotsky argued that cognitive development occurs through social interactions, particularly with more knowledgeable others (MKOs) such as parents, teachers, or skilled peers.

He introduced the concept of the Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD), which represents the gap between what a child can do independently and what they can achieve with guidance.

Furthermore, Vygotsky viewed language as fundamental to thought development, asserting that social dialogue becomes internalized as inner speech, driving cognitive processes. This perspective highlights how cultural tools, especially language, shape thinking.

Emotional factors, including motivation, self-esteem, and relationships, also play significant roles in learning and development – aspects not thoroughly addressed in Piaget’s cognitive-focused theory.

This social-emotional dimension of development has gained increasing recognition in modern educational and developmental psychology.

Underestimating children’s abilities

Piaget failed to distinguish between competence (what a child can do) and performance (what a child can show when given a particular task).

When tasks were altered, performance (and therefore competence) was affected. Therefore, Piaget might have underestimated children’s cognitive abilities.

For example, a child might have object permanence (competence) but still be unable to search for objects (performance). When Piaget hid objects from babies, he found that it wasn’t until after nine months that they looked for them.

However, Piaget relied on manual search methods – whether the child was looking for the object or not.

Later, researchers such as Baillargeon and Devos (1991) reported that infants as young as four months looked longer at a moving carrot that didn’t do what it expected, suggesting they had some sense of permanence, otherwise they wouldn’t have had any expectation of what it should or shouldn’t do.

Jean Piaget’s Legacy and Ongoing Influence

Piaget’s ideas on developmental psychology have had an enormous influence. He changed how people viewed the child’s world and their methods of studying children.

He inspired many who followed and took up his ideas. Piaget’s ideas have generated a huge amount of research, which has increased our understanding of cognitive development.

Theory

- Seminal Theory: Piaget (1936) was one of the first psychologists to study cognitive development systematically. His contributions include a stage theory of child cognitive development, detailed observational studies of cognition in children, and a series of simple but ingenious tests to reveal different cognitive abilities.

- Neo-Piagetian theories: Researchers have built upon Piaget’s stage theory of cognitive development, incorporating information processing and brain development to explain cognitive growth, emphasizing individual differences and more gradual developmental progressions (Case, 1985; Fischer, 1980; Pascual-Leone, 1970).

Impact on Educational Practices

- Early Childhood Education: Piaget’s theories underpin many early childhood programs that emphasize play-based learning, sensory experiences, and exploration.

- Constructivist Pedagogy: Piaget’s idea that children construct knowledge through interaction with their environment led to a shift from teacher-centered to child-centered approaches. This emphasizes exploration, discovery, and hands-on activities.

- Tailored Curriculum: Developmentally appropriate practice (DAP) ensures that educational experiences match children’s developmental stages, promoting optimal learning and growth. By understanding Piaget’s stages, educators can create environments and activities that challenge children appropriately. The National Association for the Education of Young Children (NAEYC ) has incorporated Piagetian principles into its DAP framework, influencing early childhood education policies worldwide.

Parenting Practices

Piaget’s theory influenced parenting by emphasizing stimulating environments, play, and supporting children’s curiosity.

Parents can use Piaget’s stages to have realistic developmental expectations of their children’s behavior and cognitive capabilities.

For instance, understanding that a toddler is in the pre-operational stage can help parents be patient when the child is egocentric.

Play Activities

Recognizing the importance of play in cognitive development, many parents provide toys and games suited for their child’s developmental stage.

Parents can offer activities that are slightly beyond their child’s current abilities, leveraging Vygotsky’s concept of the “Zone of Proximal Development,” which complements Piaget’s ideas.

Sensorimotor Stage (0-2 years):

- Peek-a-boo: Helps with object permanence.

- Texture Touch: Provide different textured materials (soft, rough, bumpy, smooth) for babies to touch and feel.

- Sound Bottles: Fill small bottles with different items like rice, beans, bells, and have children shake and listen to the different sounds.

Preoperational Stage (2-7 years):

- Memory Games: Using cards with pictures, place them face down, and ask students to find matching pairs.

- Role Playing and Pretend Play: Let children act out roles or stories that enhance symbolic thinking. Encourage symbolic play with dress-up clothes, playsets, or toy cash registers. Provide prompts or scenarios to extend their imagination.

- Story Sequencing: Give children cards with parts of a story and have them arranged in the correct order.

Concrete Operational Stage (7-11 years):

- Number Line Jumps: Create a number line on the floor with tape. Ask students to jump to the correct answer for math problems.

- Classification Games: Provide a mix of objects and ask students to classify them based on different criteria (e.g., color, size, shape).

- Logical Puzzle Games: Games that involve problem-solving using logic, such as simple Sudoku puzzles or logic grid puzzles.

Formal Operational Stage (11 years and older):

- Debate and Discussion: Provide a topic and let students debate the pros and cons. This promotes abstract thinking and logical reasoning.

- Hypothesis Testing Games: Present a scenario and have students come up with hypotheses and ways to test them.

- Strategy Board Games: Games like chess, checkers, or Settlers of Catan can help in developing strategic and forward-thinking skills.

Comparing Jean Piaget’s Ideas with Other Theorists

Integrating diverse theories enables early years professionals to develop a comprehensive view of child development.

This allows for creating holistic learning experiences that support cognitive, social, and emotional growth.

By recognizing various developmental factors, professionals can tailor their practices to each child’s unique needs and background.

Comparison with Lev Vygotsky

Differences:

- Individualvs. Social Emphasis: Piaget maintains that cognitive development stems largely from independent explorations in which children construct knowledge of their own. Vygotsky argues that children learn through social interactions, building knowledge by learning from more knowledgeable others, such as peers and adults. In other words, Vygotsky believed that culture affects cognitive development.

- Stage-Based vs Continuous Development: Piaget proposed a stage-based model of cognitive development, while Vygotsky viewed development as a continuous process influenced by social and cultural factors.

- Role of Language: For Piaget, language is considered secondary to action, i.e., thought precedes language. Vygotsky argues that the development of language and thought go together and that the origin of reasoning has more to do with our ability to communicate with others than with our interaction with the material world.

- Discovery Learning vs. Guided Scaffolding: Piaget argued that the teacher should provide opportunities that challenge the children’s existing schemas and encourage them to discover for themselves. Alternatively, Vygotsky would recommend that teachers assist the child to progress through the zone of proximal development by using scaffolding.

Similarities:

- Both theories view children as actively constructing their own knowledge of the world; they are not seen as just passively absorbing knowledge.

- They also agree that cognitive development involves qualitative changes in thinking, not only a matter of learning more things.

| Piaget | Vygotsky |

|---|

| Sociocultural | Little emphasis | Strong emphasis |

|---|

| Constructivism | Cognitive constructivist | Social constructivist |

|---|

| Stages | Cognitive development follows universal stages | Cognitive development is dependent on social context (no stages) |

|---|

| Learning & Development | The child is a “lone scientist”, develops knowledge through own exploration | Learning through social interactions. Child builds knowledge by working with others |

|---|

| Role of Language | Thought drives language development | Language drives cognitive development |

|---|

| Role of the Teacher | Provide opportunities for children to learn about the world for themselves (discovery learning) | Assist the child to progress through the ZPD by using scaffolding |

|---|

Comparison with Erik Erikson

Erikson’s (1958) psychosocial theory outlines 8 stages of psychosocial development from infancy to late adulthood.

At each stage, individuals face a conflict between two opposing states that shapes personality. Successfully resolving conflicts leads to virtues like hope, will, purpose, and integrity. Failure leads to outcomes like mistrust, guilt, role confusion, and despair.

Differences:

- Cognitive vs. Psychosocial Focus: Piaget focuses on cognitive development and how children construct knowledge. Erikson emphasizes psychosocial development, exploring how social interactions shape personality and identity.

- Universal Stages vs. Cultural Influence: Piaget proposed universal cognitive stages relatively independent of culture. Erikson’s psychosocial stages, while sequential, acknowledge significant cultural influence on their expression and timing.

- Role of Conflict: Piaget sees cognitive conflict (disequilibrium) as a driver for learning. Erikson views psychosocial crises as essential for personal growth and identity formation.

- Scope of Development: Piaget’s theory primarily covers childhood to adolescence. Erikson’s theory spans the entire lifespan, from infancy to late adulthood.

- Learning Process vs. Identity Formation: Piaget emphasizes how children learn and understand the world. Erikson focuses on how individuals develop their sense of self and place in society through resolving psychosocial conflicts.

Similarities:

- Stage-based theories: Both propose that development occurs in distinct stages (Gilleard & Higgs, 2016).

- Age-related progression: Stages are generally associated with specific age ranges.

- Cumulative development: Each stage builds upon the previous ones.

- Focus on childhood: Both emphasize the importance of early life experiences.

- Active role of the individual: Both see children as active participants in their development.

Comparison with Urie Bronfenbrenner

Bronfenbrenner’s (1979) ecological systems theory posits that an individual’s development is influenced by a series of interconnected environmental systems, ranging from the immediate surroundings (e.g., family) to broad societal structures (e.g., culture).

Bronfenbrenner’s theory offers a more comprehensive view of the multiple influences on a child’s development, complementing Piaget’s focus on cognitive processes with a broader ecological perspective.

Differences:

- Individual vs. Ecological Emphasis: Piaget focuses on individual cognitive development through independent exploration. Bronfenbrenner emphasizes the complex interplay between an individual and multiple environmental systems, from immediate family to broader societal influences.

- Stage-based vs. Systems Approach: Piaget proposed distinct stages of cognitive development. Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory views development as ongoing interactions between the individual and various environmental contexts throughout the lifespan.

- Role of Environment: For Piaget, the environment provides opportunities for cognitive conflict and schema development. Bronfenbrenner sees the environment as a nested set of systems (microsystem, mesosystem, exosystem, macrosystem, chronosystem) that directly and indirectly influence development.

- Cognitive Structures vs. Proximal Processes: Piaget focused on the development of cognitive structures (schemas). Bronfenbrenner emphasized proximal processes – regular, enduring interactions between the individual and their immediate environment – as key drivers of development.

- Discovery Learning vs. Contextual Learning: Piaget advocated for discovery learning to challenge existing schemas. Bronfenbrenner would emphasize the importance of understanding and leveraging the various ecological contexts in which learning occurs, from family to cultural systems.

Similarities:

- Both recognize the child as an active participant in development.

- Both acknowledge the importance of the child’s environment in shaping development.

FAQs

What is cognitive development?

Cognitive development is how a person’s ability to think, learn, remember, problem-solve, and make decisions changes over time.

This includes the growth and maturation of the brain, as well as the acquisition and refinement of various mental skills and abilities.

Cognitive development is a major aspect of human development, and both genetic and environmental factors heavily influence it. Key domains of cognitive development include attention, memory, language skills, logical reasoning, and problem-solving.

Various theories, such as those proposed by Jean Piaget and Lev Vygotsky, provide different perspectives on how this complex process unfolds from infancy through adulthood.

What are the 4 stages of Piaget’s theory?

Piaget divided children’s cognitive development into four stages; each of the stages represents a new way of thinking and understanding the world.

He called them (1) sensorimotor intelligence, (2) preoperational thinking, (3) concrete operational thinking, and (4) formal operational thinking. Each stage is correlated with an age period of childhood, but only approximately.

According to Piaget, intellectual development takes place through stages that occur in a fixed order and which are universal (all children pass through these stages regardless of social or cultural background).

Development can only occur when the brain has matured to a point of “readiness”.

What are some of the weaknesses of Piaget’s theory?

Cross-cultural studies show that the stages of development (except the formal operational stage) occur in the same order in all cultures suggesting that cognitive development is a product of a biological maturation process.

However, the age at which the stages are reached varies between cultures and individuals, suggesting that social and cultural factors and individual differences influence cognitive development.

What are Piaget’s concepts of schemas?

Schemas are mental structures that contain all of the information relating to one aspect of the world around us.

According to Piaget, we are born with a few primitive schemas, such as sucking, which give us the means to interact with the world.

These are physical, but as the child develops, they become mental schemas. These schemas become more complex with experience.

References

- Baillargeon, R., & DeVos, J. (1991). Object permanence in young infants: Further evidence. Child development, 1227-1246.

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. Harvard University Press.

- Bruner, J. S. (1966). Toward a theory of instruction. Cambridge, Mass.: Belkapp Press.

- Case, R. (1985). Intellectual development: Birth to adulthood. Academic Press.

- Cuban, L., Kirkpatrick, H., & Peck, C. (2001). High access and low use of technologies in high school classrooms: Explaining an apparent paradox. American Educational Research Journal, 38(4), 813-834.

- Daniels, H., & Diack, H. (1977). Piagetian tests for the primary school. Routledge and Kegan Paul.

- Dasen, P. (1994). Culture and cognitive development from a Piagetian perspective. In W .J. Lonner & R.S. Malpass (Eds.), Psychology and culture (pp. 145–149). Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon.

- Donaldson, M. (1978). Children’s minds. Fontana Press.

- Fisher, K., Hirsh-Pasek, K., Golinkoff, R. M., Singer, D. G., & Berk, L. (2011). Playing around in school: Implications for learning and educational policy. In A. D. Pellegrini (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of the development of play (pp. 341-360). Oxford University Press.

- Erickson, E. H. (1958). Young man Luther: A study in psychoanalysis and history. New York: Norton.

- Gehlbach, H. (2010). The social side of school: Why teachers need social psychology. Educational Psychology Review, 22, 349-362.

- Guy-Evans, O. (2024, January 17). Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory. Simply Psychology. https://www.simplypsychology.org/bronfenbrenner.html

- Hughes, M. (1975). Egocentrism in preschool children. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. Edinburgh University.

- Inhelder, B., & Piaget, J. (1958). The growth of logical thinking from childhood to adolescence. New York: Basic Books.

- Keating, D. (1979). Adolescent thinking. In J. Adelson (Ed.), Handbook of adolescent psychology (pp. 211-246). New York: Wiley.

- Kegan, R. (1982). The evolving self: Problem and process in human development. Harvard University Press.

- Lee, K., & Zentall, S. S. (2012). Psychostimulant and sensory stimulation interventions that target the reading and math deficits of students with ADHD. Journal of Attention Disorders, 16(4), 308-329.

- Nielsen. 2014. “Millennials: Technology = Social Connection.” http://www.nielsen.com/content/corporate/us/en/insights/news/2014/millennials-technology-social-connecti on.html.

- Lourenço, O. (2012). Piaget and Vygotsky: Many resemblances, and a crucial difference. New Ideas in Psychology, 30(3), 281-295.

- Lourenço, O., & Machado, A. (1996). In defense of Piaget’s theory: A reply to 10 common criticisms. Psychological Review, 103(1), 143-164.

- Morra, S., & Borella, E. (2015). Working memory training: From metaphors to models. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 1097.

- McLeod, S. (2024, January 24). Vygotsky’s Theory Of Cognitive Development. Simply Psychology. https://www.simplypsychology.org/vygotsky.html

- McLeod, S. (2024, January 24). Piaget’s Sensorimotor Stage of Cognitive Development. Simply Psychology. https://www.simplypsychology.org/sensorimotor.html

- McLeod, S. (2024, January 24). Piaget’s Preoperational Stage (Ages 2-7). Simply Psychology. https://www.simplypsychology.org/preoperational.html

- McLeod, S. (2024, January 24). The Concrete Operational Stage of Cognitive Development. Simply Psychology. https://www.simplypsychology.org/concrete-operational.html

- McLeod, S. (2024, January 24). Piaget’s Formal Operational Stage: Definition & Examples. Simply Psychology. https://www.simplypsychology.org/formal-operational.html

- McLeod, S. (2024, January 25). Erik Erikson’s Stages Of Psychosocial Development. Simply Psychology. https://www.simplypsychology.org/erik-erikson.html

- Ojose, B. (2008). Applying Piaget’s theory of cognitive development to mathematics instruction. The Mathematics Educator, 18(1), 26-30.

- Pascual-Leone, J. (1970). A mathematical model for the transition rule in Piaget’s developmental stages. Acta Psychologica, 32, 301-345.

- Passey, D. (2013). Inclusive technology enhanced learning: Overcoming cognitive, physical, emotional, and geographic challenges. Routledge.

- Piaget, J. (1932). The moral judgment of the child. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

- Piaget, J. (1936). Origins of intelligence in the child. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

- Piaget, J. (1945). Play, dreams and imitation in childhood. London: Heinemann.

- Piaget, J. (1952). The child’s conception of number. Routledge & Kegan Paul.

- Piaget, J. (1952). The origins of intelligence in children. (M. Cook, Trans.). W W Norton & Co. (Original work published 1936)

- Piaget, J. (1957). Construction of reality in the child. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

- Piaget, J., & Cook, M. T. (1952). The origins of intelligence in children. New York, NY: International University Press.

- Piaget, J. (1962). The language and thought of the child (3rd ed.). (M. Gabain, Trans.). Routledge & Kegan Paul. (Original work published 1923)

- Piaget, J. (1981). Intelligence and affectivity: Their relationship during child development.(Trans & Ed TA Brown & CE Kaegi). Annual Reviews.

- Piaget, J. (1985). The equilibration of cognitive structures: The central problem of intellectual development. (T. Brown & K. J. Thampy, Trans.). University of Chicago Press. (Original work published 1975)

- Piaget, J., & Inhelder, B. (1956). The child’s conception of space. Routledge & Kegan Paul.

- Piaget, J., & Szeminska, A. (1952). The child’s conception of number. Routledge & Kegan Paul.

- Plowden, B. H. P. (1967). Children and their primary schools: A report (Research and Surveys). London, England: HM Stationery Office.

- Rogoff, B. (2003). The cultural nature of human development. Oxford University Press.

- Shayer, M. (1997). The Long-Term Effects of Cognitive Acceleration on Pupils’ School Achievement, November 1996.

- Siegler, R. S., DeLoache, J. S., & Eisenberg, N. (2003). How children develop. New York: Worth.

- Smith, L. (Ed.). (1996). Critical readings on Piaget. London: Routledge.

- Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Wadsworth, B. J. (2004). Piaget’s theory of cognitive and affective development: Foundations of constructivism. New York: Longman.

Further Reading

- BBC Radio Broadcast about the Three Mountains Study

- Piagetian stages: A critical review

- Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory